Disclaimer: The contents of this article are intended to provide a general understanding of the subject matter. However, this article is not intended to provide legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied on as such.

The FinCEN “Travel Rule” has many requirements and nuances that can challenge and confuse new and seasoned AML compliance professionals alike. From the basics of what types of transactions fall under the Rule, to mandatory versus optional data requirements, to its many exemptions – as well as the nuances addressed by subsequent FinCEN guidance not contained in the Rule itself – compliance professionals need to understand the details of this longstanding Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) regulation.

This article begins with a review of the fundamentals of the FinCEN Travel Rule, and why compliance is so important to anti-money laundering efforts. Learn about the nuances of complying with the Travel Rule, including a discussion of pending changes to the Travel Rule in an October 2020 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking; Fedwire versus Travel Rule requirements; aggregated funds transfers; Originator name issues; and transfers by non-customers.

What is the FinCEN Travel Rule?

In January 1995, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and FinCEN jointly issued a Rule for banks and other nonbank financial institutions, relating to information required to be included in funds transfers. The Rule is comprised of two parts – the Recordkeeping Rule, and what’s come to be known as the Travel Rule. The Travel Rule was promoted by FinCEN, in keeping with their mandate to enforce the Bank Secrecy Act.

| “Recordkeeping Rule” Requires financial institutions to collect and retain certain information related to funds transfers and transmittals in amounts of $3,000 or more. 31 CFR 1020.410(a) and 1010.410(e) |

“Travel Rule” Requires financial institutions to transmit certain information on certain funds transfers and transmittals to other financial institutions participating in the transfer or transmittal. 31 CFR 1010.410(f) |

The Recordkeeping Rule and the Travel Rule are complementary. The Recordkeeping Rule requires financial institutions to collect and retain the information that in turn, per the Travel Rule, must be included with a funds transfer and passed along – or “travel” – to each successive bank in the funds transfer chain. The Recordkeeping Rule does however serve other purposes besides ensuring that information is available to include with funds transfers.

The terms “transfer” and “transmittal” are used throughout this regulation. The distinction between these two terms is simple: a bank performs transfers, and a non-bank financial institution performs transmittals. The term “transfer” will primarily be used from this point on to refer to both types of transactions.

The Underlying Objective

Fund transfers have been the tool of choice for money laundering, fraud, and much more, for decades. As FinCEN’s mission is to implement, administer, and enforce compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act, it has the authority to require financial institutions to keep records that, according to FinCEN, have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or even in intelligence or counterintelligence matters when terrorism is involved.

Ultimately, the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is primarily designed to help law enforcement to detect, investigate and prosecute money laundering and financial crimes, by preserving the information trail about who’s sending and receiving money through funds transfer systems. In other words, it helps them follow the money.

Transactions Subject to the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule

The Recordkeeping and Travel Rule states that it applies to funds transfers. The definition of a funds transfer is very important, as highlighted later in the discussion of the most recent Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.

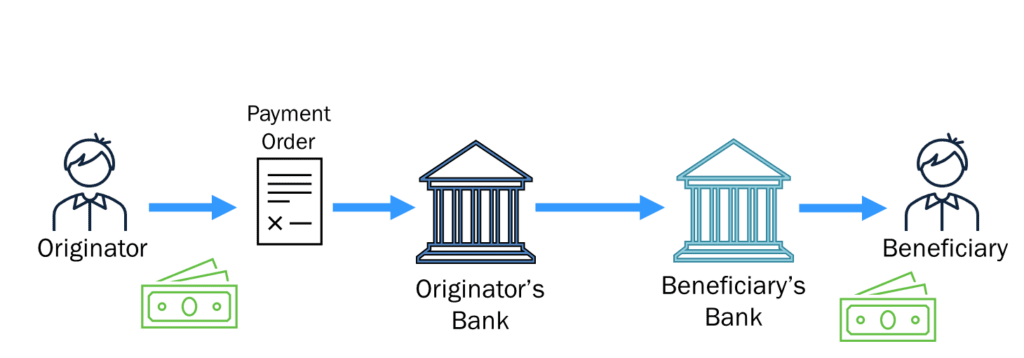

The Rule defines a funds transfer as a series of transactions, beginning with the Originator’s payment order, made for the purpose of making a payment of money to the Beneficiary of that payment order.

Below is a basic illustration of a funds transfer. An Originator creates a Payment Order to pay money to a specific Beneficiary. The Originator delivers the Payment Order to his bank, which then passes on the Payment Order details to the bank holding the Beneficiary’s account. The funds transfer is complete when the Beneficiary’s Bank accepts the Payment Order on behalf of the Beneficiary.

In today’s world, funds transfers are electronic, and a wire transfer is the most common form of electronic funds transfer. At its essence, a wire transfer is simply a message from one bank to another, passed through an electronic system, such as Fedwire, SWIFT, or CHIPS.

Electronic Funds Transfers That are Excluded

Besides wire transfers, there are many types of electronic funds transfers, or EFTs in use today. Although all are in essence funds transfers, these types of transactions are specifically excluded from the definition of a funds transfer or transmittal in the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. Instead, these types of electronic funds transfers are defined in, and governed by, the Electronic Funds Transfer Act, otherwise known as Regulation E.[i] Currently, these are:

- ACH (automated clearing house) transactions

- ATM (automated teller machine) transactions

- Point of Sale (POS) transactions

- Direct deposits or withdrawals

- Telephone banking transfers

Terminology Review

The terminology used in the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is in many cases unique. The more commonly-used terms when referring to wire transfers and other electronic funds transfers come from the Uniform Commercial Code’s Article 4A, which governs funds transfers.[ii]

Throughout this article, UCC 4A terminology will be used as it is more commonly understood:

| Recordkeeping & Travel Rule: | UCC 4A: |

| Transmittal of Funds | Funds Transfer |

| Transmittal Order | Payment Order |

| Transmittor* | Originator |

| Transmittor’s* Financial Institution | Originator’s Bank |

| Intermediary Financial Institution | Intermediary Bank |

| Recipient’s Financial Institution | Beneficiary’s Bank |

| Recipient | Beneficiary |

| Receiving Financial Institution | Receiving Bank |

| Sender | Sender |

* The spelling shown here is per the regulation; it is not the correct spelling of this word according to widely-accepted sources.

The term Sender per UCC 4A refers to the person who is delivering the Payment Order to the Receiving Bank. This person would typically be the Originator, but could potentially be a third party, as discussed further below.

Funds Transfer Data Requirements

The Rule divides the data requirements on a funds transfer into two groups: (1) data that is mandatory, and (2) data that, if the originator provides it, must be included.

First, the data that must be included on the funds transfer by the Originator’s Bank is:

- The Originator’s name

- The Originator’s address

- The Originator’s account number (if there is one)

- The identity of the Beneficiary’s Bank

- The payment amount

- The payment execution date

Typically, a bank will automatically populate the Originator’s name and address information on a wire transfer directly from the customer record. This is because it is very important that the Originator’s name reflects the actual party initiating the Payment Order. (This topic is explored further in the Deep Dives section below.)

The second group of data elements is optional – meaning, if the Originator provides any of this information, it must be included on the funds transfer record. This information includes:

- The Recipient’s (or Beneficiary’s) name

- The Beneficiary’s address

- The Beneficiary’s account number or other identifiers

- Any other message or payment instructions – what typically are entered in the freeform text fields on a wire transfer, such as the Originator to Beneficiary Information or OBI field on a Fedwire.

Even though this information is not mandatory per FinCEN’s Travel Rule requirements, nothing precludes a bank from mandating customers to supply it. From an operational perspective, at least the Beneficiary’s account number should be required information to minimize the risk that the transfer will be rejected and returned by the Receiving Bank as unpostable.

As well as being highly valuable to law enforcement, Beneficiary information is critical to a bank’s fraud detection, suspicious activity monitoring and sanctions compliance efforts. Without this information, detecting an unusual or suspicious wire transfer recipient, establishing a pattern of transaction activity to a particular recipient, or identifying a customer transaction with an OFAC-sanctioned party is impossible.

Exemptions from the Travel Rule

In addition to the types of EFTs that are not subject to the Rule (as they fall under the jurisdiction of Regulation E) there are several categories, or classes, of funds transfers that are exempt from FinCEN’s Travel Rule’s requirements. Specifically:

- A funds transfer that is less than $3,000.

- A funds transfer where the sender and the recipient are the same person. For example, if an individual is wiring money from her account at Bank A to her account at Bank B, Bank A does not have to obtain and retain the Travel Rule mandatory information for this transfer.

- A funds transfer made between two account holders at the same institution. Commonly known as a book transfer, this transaction is not processed through the Federal Reserve, but is simply a journal entry on the financial institution’s books.

- Funds transfers between any two of these types of entities need not meet the Rule’s requirements:

- A bank, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- A commodities/futures broker, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- The U.S. government; a state or local government

- A securities broker/dealer, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- A mutual fund

- A federal, state or local government agency or instrumentality

Nothing prevents a financial institution from ignoring these exemptions; the institution is free to follow the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule requirements with every funds transfer. Such a practice benefits all the financial institutions involved in the transaction, as well as law enforcement.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Enforcement

FinCEN enforcement actions over the years have never solely targeted violations of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. This is likely because as a matter of operational efficiency, financial institutions typically populate the basic mandatory information on all outgoing funds transfers and maintain records of such.

However, it is important not to overlook the other key element of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule: records retrievability.

A financial institution may be approached by federal, state, or local law enforcement, its regulator, another regulatory agency, or by subpoena, to provide specific funds transfer records.

If the institution is the Originator’s Bank, the mandatory funds transfer information to be collected and retained (Originator name & address, etc.) must be retrievable upon request, based on the Originator’s name. If the Originator is the institution’s established customer, transaction retrieval by the Originator’s account number may also be requested. A Beneficiary’s Bank must be able to retrieve funds transfer records by the Beneficiary’s name, and if an established customer, also by account number.

The FinCEN Travel Rule requires all funds transfer records to be retained for a minimum of five years from the date of the transaction.

Once funds transfer records are requested, the Rule states they must be supplied within a reasonable period – which may likely be negotiated between the financial institution and the requestor.

The 120-Hour Rule

However, financial institutions should be aware of a lesser-known clause within Section 314 of the USA PATRIOT Act that could impact records retrieval. Commonly known as the 120 Hour Rule, it states that any information, on any account that is opened, maintained, or managed in the U.S. requested by a federal banking agency, must be provided by the financial institution within 120 hours (5 days) after receiving the request. Funds transfer records would likely fall within the scope of this Rule.

Anecdotally, regulators have not imposed the 120 Hour Rule often. Financial institutions should nevertheless be prepared to respond to regulatory or law enforcement requests as quickly and efficiently as possible. IRS and civil case subpoenas requesting funds transfer records also typically have a short response window.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Guidance: A Deep Dive

The following sections explore deeper topics relating to Recordkeeping and Travel Rule guidance, including:

- The October 2020 Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking impacting the Rule

- Fedwire versus the Travel Rule

- Originator name issues

- Aggregated funds transfers

- Funds transfers for non-customers

Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

On October 23, 2020, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and FinCEN issued a Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) to amend the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule regulations. Written comments on the Proposed Rule were due by the end of November 2020. The next step is a publication of the Final Rule, but FinCEN has not set a date for this.

According to the website Regulations.gov, 2,882 comments were submitted for the NPRM. Commenters ranged from major banking groups such as the American Bankers Association to private individuals. The comments were overwhelmingly negative.

The NPRM proposes two major changes, discussed below.

Reducing the Minimum Dollar Threshold for Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Compliance on Cross-Border Funds Transfers

Part 1 of the NPRM proposes reducing the $3,000 threshold for Recordkeeping and Travel Rule compliance to $250 for cross-border transactions. The threshold for domestic transactions would remain at $3,000.

While this change may not have a major impact on financial institutions that ignore the dollar threshold exemption, it would significantly impact those institutions that follow it. There are some interesting nuances in this proposed change regarding what is meant by “cross border.”

Initially, a “cross-border” transaction is defined as one that, “begins or ends outside of the United States.” The United States includes the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the Indian lands (as that term is defined in the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act), and the Territories and Insular Possessions of the United States.[iii]

A funds transfer would be considered to “begin or end outside the United States” if the financial institution knows, or has reason to know, that the Originator, the Originator’s financial institution, the Recipient/Beneficiary, or the Recipient/Beneficiary’s financial institution is located in, is ordinarily resident in, or is organized under the laws of a jurisdiction other than the United States. Furthermore, a financial institution would have “reason to know” that a transaction begins or ends outside the United States only to the extent such information could be determined based on the information it receives in the payment order or otherwise collects from the Originator.

The driving factor behind this regulatory change is the benefit to law enforcement and national security. FinCEN’s analysis of SAR filings, as well as comments collected by the Department of Justice from agents and prosecutors at the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Secret Service, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, all supported lowering (or eliminating altogether) the reporting threshold, in order to disrupt illegal activity and increase its cost to the perpetrators.

According to FinCEN and these other law enforcement agencies, cross-border funds transfers, and especially lower dollar transfers in the $200 to $600 dollar range, are being used extensively in terrorist financing and narcotics trafficking to avoid reporting and detection.

For those institutions that abide by the minimum reporting threshold, the new lower cross-border threshold presents operational and programmatic challenges. The distinction between a cross-border and a domestic transaction is not always clear. For example, if a financial institution has no direct foreign correspondent banking relationships, its cross-border funds transfers must flow through a U.S. intermediary institution, and therefore the Federal Reserve. Automated systems may interpret such transactions as domestic because the first receiving institution will always be U.S.-based.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Applies to Virtual Currency

The second element of the NPRM would make funds transfers involving convertible virtual currency (CVC) and other digital assets, to be subject to the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. CVC, more commonly known as cryptocurrency or cyber-currency, is a medium of exchange with an equivalent value in currency or acts as a substitute for currency, but at present does not fall under the regulatory definition of “money” (also known as legal tender).

The Proposed Rule now defines CVC as money. This is significant because transfers of CVC now legally fall within the meaning of “a transfer of money” to which the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule applies.

The “why” behind this aspect of the Proposed Rule is the exponential growth in CVC use for money laundering, terrorist financing, organized crime, weapons proliferation, and sanctions evasion. CVC’s anonymity makes it particularly attractive for financial crime. Bad actors can convert illegal proceeds into virtual currency and then transmit it to any destination anonymously within seconds, where it is redeemed for cash again or converted to another form. This makes CVC a perfect mechanism for the layering phase of money laundering.

For more information, check out our blog on the crypto travel rule.

NPRM Background and the “FATF Travel Rule”

Events leading up to the NPRM provide an interesting background, especially as they are intertwined with global anti-money laundering efforts – specifically those of the Financial Actions Task Force (FATF) and what has come to be known as the “FATF Travel Rule.”

As virtual currency’s popularity began to grow exponentially, regulators in the United States and globally were caught off-guard. It was not well understood, and there were no real protocols in place to govern it. In March 2013, FinCEN released initial guidance clarifying that virtual currency exchangers and administrators must register as money service businesses, pursuant to federal law.[iv]

In October 2018, FATF published guidance that clearly defined just what are virtual assets and virtual asset service providers (VASPs).[v] FATF followed this up in February 2019 with a far-reaching Interpretive Note to Recommendation 15 (New Technologies), in a Public Statement titled “Mitigating Risks from Virtual Assets.”[vi]

This publication included two key proposals that generated backlash from the cryptocurrency sector:

For one, it proposed that VASPs should, at a minimum, be required to be licensed or registered in the jurisdiction(s) where they are created. As well, VASPs should be subject to effective systems for monitoring compliance with a country’s AML/CFT requirements, and be supervised by a competent authority – not a self-regulatory body.

Second, it introduced what’s come to be known as the FATF Travel Rule for funds transferred over $1,000 – specifically referencing virtual asset transfers. These requirements match up point-for-point with the United States Recordkeeping and Travel Rule in terms of required funds transfer data to be obtained, retained and passed on.

In May 2019, FinCEN published lengthy and complex guidance[vii] effectively stating that CVC-based transfers processed by nonbank financial institutions that meet the definition of a money service business are subject to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), and thereby the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. Furthermore, it clarified that a transfer of virtual currency involves a sender making a “transmittal order.”

One month later in June 2019, the FATF formally adopted the proposals from their 2018 guidance by incorporating them into the FATF 40 Recommendations – specifically, Recommendation 16, Wire Transfers.

In October 2020, the Federal Reserve Board and FinCEN issued their Joint NPRM, which would codify their May 2019 guidance as well.

Fedwire vs. the FinCEN Travel Rule

With respect to the implementation and enforcement of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule, there is an interesting disconnect between the two key divisions of the U.S. Treasury Department. FinCEN is tasked with administering and enforcing the BSA, of which the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is a part. The Federal Reserve Banks, also part of the US Treasury Department, own and operate Fedwire, the country’s primary funds transfer service. Yet the Fedwire system does no validation whatsoever that funds transfers processed through it include the basic, mandatory information required by the Travel Rule. The only data elements required to process a Fedwire transfer are the sending and receiving banks’ Fed routing numbers, the transaction amount, and its effective date.[viii]

One might conclude that law enforcement could have much more information on funds transfers at its disposal if the federal government’s actual funds transfer system made that information required. Today, should an Originator’s Bank fail to include the Travel Rule’s mandatory information (Originator’s name and address, etc.) on a funds transfer, the Receiving Bank is under no obligation to return the transfer and request the mandatory information. Instead, the burden is solely on the Originator’s Bank to comply, and any subsequent Receiving Banks’ responsibility is simply to retain (and pass on, if necessary) the information received.

Aggregated Funds Transfers

A financial institution may aggregate, or combine, multiple individual funds transfer requests into a single, aggregated funds transfer/transmittal.

For purposes of the FinCEN Travel Rule, whenever a financial institution aggregates multiple parties’ transfer requests into one single transfer, the institution itself becomes the Originator. Similarly, if there are multiple Beneficiaries in this aggregated transfer, but all with accounts at the same Receiving institution, then that institution becomes the Beneficiary on the aggregated funds transfer.

Aggregated funds transfers are common with money service businesses, as illustrated here:

A money service business (MSB) in Texas has several transmittal orders from various individuals, who are all sending funds to recipients via one particular Mexican casa de cambio. The Texas MSB aggregates these transactions into a single transmittal order, submitted to the MSB’s bank in Texas, for which the Beneficiary is the Mexican casa de cambio. This transmittal order does not identify the individual Originators or Beneficiaries of the underlying transfers. The Texas bank passes on the aggregated transmittal order to the Mexican bank holding the account of the casa de cambio. Once this funds transfer is complete, the casa de cambio pays the Mexican recipients, based on separate individual transmittal orders it received directly from the Texas MSB.

In this aggregated funds transfer scenario, the Originators’ payments are completed through a combination of individual transmittal orders between the senders and recipients, and an aggregated funds transfer between the MSB and the casa de cambio.

To summarize, the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule requirements for the Texas MSB and its Texas bank are as follows.

The MSB must keep a record of each customer’s individual transmittal order. The MSB is the Originator’s Bank, and the individual sender is the Originator. The Beneficiary is the individual who will receive the money, and the Beneficiary’s Bank is the Mexican casa de cambio.

The Texas bank must retain and pass on the information on the aggregated funds transfer between the MSB and the casa de cambio. On this funds transfer record, the Originator is the Texas MSB, the Texas bank is the Originator’s Bank, the Mexican casa de cambio is the Beneficiary, and its bank is the Beneficiary’s Bank.

Originator Name Issues

The Originator’s full true name is a required data element per the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. A financial institution will typically populate the Originator’s name and address information on a funds transfer directly from its customer record.

A financial institution may be faced with a situation where a customer does not want his/her/their actual name to be present on a funds transfer.

For example, a customer may ask the financial institution to replace the Originator name on a funds transfer with that of some other party. Oftentimes, the customer is sending funds from their own account on behalf of someone else. Individuals as well as business entities may make such a request, for a variety of underlying reasons.

Changing an Originator’s name from that of the account holder to that of a third party is clearly a violation of the spirit of the Travel Rule, although not specifically addressed within it. Further, it exposes the financial institution to risks of abetting fraud, tax evasion, and other illicit activities.

The FinCEN Travel Rule does, however, specifically prohibit the use of a code name or pseudonym in place of an individual Originator’s true name. However, there are some exceptions to this with respect to commercial/business customers. For instance, a business may have several accounts, each of which is titled in a manner that reflects the purpose of the account – such as “Acme Corporation Payroll Fund.” Use of an account name that reflects its commercial purpose is acceptable for an Originator name under the Travel Rule.

Other acceptable Originator names for business customers are names of unincorporated divisions or departments, trade names, and Doing Business As (DBA) names, such as these examples:

- “Giant Inc Engineering Division”

- “McDonald’s” (a trade name for the McDonald’s Corporation)

- “Sue’s Flowers” (the DBA name for a sole proprietorship owned by Sue Smith)

Joint Accounts

When a funds transfer is made from a joint account, technically both account holders are the Originators. However, automated funds transfer systems, including Fedwire, do not provide space for more than one Originator name and address. FinCEN provides financial institutions with a solution:[ix] simply identify the Originator on the transfer as the joint account holder who requested it.

Funds Transfers for Non-Customers

Additional rules apply when a financial institution accepts a funds transfer order from a party that is not an established customer (i.e., a non-customer).

If the payment order is made in person by the Originator, the financial institution must verify his/her identity, and obtain and retain the following information:

- Originator’s name and address

- Type of identification document reviewed, and its number and other details (e.g., driver’s license number, state where issued)

- The Originator’s tax ID number, or, if none, an alien identification number or passport number and country of issuance. Should the Originator state that he/she has no tax ID number, a record of this fact should also be retained.

If the person delivering the payment order is not the Originator, the financial institution should record that person’s name, address, and tax ID number (or alternative as described above), or note the lack thereof. The institution should also request the actual Originator’s tax ID number (or alternative as described above) or a notation of the lack thereof. The institution must also keep a record of the method of payment for the funds transfer (such as a check or credit card transaction).

Summary

- The Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is a joint regulation under the Bank Secrecy Act, issued by the Federal Reserve Board and FinCEN.

- Record retrieval is equally important as record creation. Financial institutions should ensure full records of all outgoing and incoming funds transfers are retained for five years and can be retrieved by Originator name or account number (for established customers).

- Exemptions to the Rule, such as funds transfers under $3,000, are not mandatory. Financial institutions may choose to fully comply with the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule for every funds transfer sent or received, no matter the dollar amount or the parties involved.

- If the Originator is not required to provide the Beneficiary’s name, address, and account number on every wire transfer, this will have a significant detrimental impact on the financial institution’s suspicious activity monitoring, fraud detection, and sanctions compliance efforts.

- The October 2020 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking impacts cross-border funds transfers and the virtual currency industry. No date has yet been set for the publication of a Final Rule.

- A customer should not be allowed to substitute another name for the Originator on an outgoing funds transfer, as this exposes the financial institution to the risk of acting as a conduit for fraud, tax evasion, and other illicit activity, no matter how innocent or legitimate the customer’s request may seem.

- A financial institution that sends or receives aggregated funds transfers, or transfers for non-customers, should examine its existing processes to ensure compliance with the special rules for these activities.

How Alessa Can Help

Alessa is an integrated AML compliance software solution for due diligence, sanctions screening, real-time transaction monitoring, regulatory reporting and more. The solution integrates with existing core systems and includes:

- Identity verification and customer due diligence for KYC/KYB

- Real-time transaction monitoring and screening

- Sanctions, PEPs, watch list, crypto and other forms of screening

- Configurable risk scoring

- Automated regulatory reporting

- Advanced analytics like anomaly detection and machine learning

- Dashboards, workflows and case management

With Alessa, customers can monitor their wire transactions and ensure that the appropriate process is in place to collect and record the right information in order to comply with regulatory bodies. Contact us today to see how we can help you implement or enhance the AML program at your financial institution to comply with mandates such as the FinCEN Travel Rule.

[i] 15 USC 1693 et seq.

[ii] The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) is a comprehensive set of laws governing all commercial transactions in the United States. It is not a federal law, but a uniformly adopted state law. Uniformity of law is essential in this area for the interstate transaction of business. Source: Uniform Law Commission, www.uniformlaws.org

[iii] 31 CFR 1010.100(hhh)

[iv] Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. “Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Persons Administering, Exchanging, or Using Virtual Currencies.” FIN-2013-G001, 18 March 2013.

[v] Financial Actions Task Force. “Regulation of Virtual Assets.” 19 October 2018.

[vi] Financial Actions Task Force. “Public Statement – Mitigating Risks from Virtual Assets.” 22 February 2019.

[vii] Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. “Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Certain Business Models Involving Convertible Virtual Currencies.” FIN-2019-G001, 9 May 2019.

[viii] Various codes are also required data on a Fedwire transfer; however, these codes are for system processing purposes and have no relation to originator or beneficiary data.

[ix] Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. “Funds ‘Travel’ Regulations: Questions and Answers.” FIN-2010-G004, 9 November 2010.